Cennin Pedr: the Roots and Reach of the Wild Daffodil

Welsh names: Cennin Pedr, Blodau Dewi, Lili Grawys, Blodyn Mawrth , Croeso Gwanyn, Gwayw’r Brenin, Clychau Babi

English name: Wild Daffodil

Scientific name: Narcissus pseudonarcissus

Ubiquitous and beloved, the golden daffodil is a national icon of Cymru. An emblem of our patron Dewi Sant (Saint David), it’s worn with pride on the first of March to commemorate his life and death. In early spring, before other flowers are awake, yellow blooms carpet city parks, woodland floors and road verges throughout the nation. The Welsh-ness of the plant is unquestionable, but the origins, history and symbolism of Narcissi extend far further and deeper than this land, posing the question: what do we know of our national flower?

Beginnings

Whether by wind or the coat of a roaming creature, the seed travels. Firmly ensconced in earth, green blades cut through cold ground, but it will be years before the beginnings of buds start to swell - two, four, even six - time spent as just a handful of slender leaves, folding in a breeze. Below ground it is busy; nimble roots extend their feelers, taking hold and searching for moisture. The pale strands are learning, connecting with other networks and systems, sharing information, nutrients and warnings.

Long ago, she was a chaste woman. The daughter of a prince, she lived piously, so they called her Non, meaning nun. One day, he came upon her; a supposed ‘noble man’ from Ceredigion. Out of aggression, the desire to subject - or simply because he could - he forced himself upon her and left, altering the trajectory of her life and legacy.

As though conjured by the violence and chaos of her situation, a storm raged on the south coast of Pembrokeshire. Pregnant and alone, she felt compelled to be in it. Stumbling towards the raging sea, holding her belly, she collapsed on the cliff edge. As lightning cracked, she gripped the rocks beneath her as she pushed him out; the marks of her pain still visible in the stone.

As the boy was born, a holy well sprang up nearby. Or so they say.

She named him Dewi; god, or beloved.

Five thousand miles to the east, the first waxing lunar crescent is just about visible. All across China, New Year celebrations begin, marking the end of winter and start of spring. Symbolic of wealth, good fortune and immortality, ‘Crab Claw Narcissus’ bulbs are brought indoors for the traditional carving. The plants are placed in shallow dishes with pebbles and water, symbolic of Daoist deities and Xiang River goddesses . Incisions are made in the bulbs which manipulate the new shoots, forcing them to them curl and twist as they grow. Plants are often decorated to resemble roosters or cranes, the former symbolic of prosperity, holiness, luck and the sun . If they flower during the New Year period, it is considered especially auspicious.

In bloom

When it is old enough, the first flower comes. Developing in the bulb, the stem emerges hollow and upright. Shedding its papery sheath, the petals unfurl to reveal the central corona; the golden trumpet, cup or bell that’s inspired many a common English name: bell flower, bell rope, gold bells, golden trumpet…

There are 36 species of daffodil and over 26,000 cultivars. The wild daffodil, Narcissus pseudonarcissus, is the only species considered native to Wales and the UK. Due to the plant’s ability to hybridise (breed with other varieties), finding true wild plants can be tricky. Though Narcissi grow abundantly in wild places, the typical fully-yellow flowers are likely hybrids of different varieties. Wild daffodils are smaller in stature, up to 35cm tall, with a deep yellow trumpet surrounded by paler, teardrop-shaped petals. Ancient woods are best for spotting the wild species, especially Coed y Bwl; an ancient Ash woodland on the Northwest side of the Alun Valley in Glamorgan .

The principal Welsh name for the wild daffodil is Cennin Pedr, literally translating to ‘Peter’s leek’. Leeks, of course, are the original botanical emblem adopted by Wales. The story goes that in the 7th century King Cadwalladwr of Gwynedd and his army were fighting off invading Saxons and in order to identify themselves against the enemy they plucked leeks from the field in which they stood, sticking them in their helmets . 17th century English poet Michael Drayton tells how it was St David himself who led the resistance against pagan Saxons, and who ordered soldiers to identify themselves with leeks . The reliability of this version is questionable and it’s possible that Drayton is one of many Englishmen to publish personally embellished versions of Welsh narratives, adding elements of Celtic fantasy to the mix.

As with daffodils, there are different varieties of leek: the wild leek, Allium ampeloprasum, bears long, needle-shaped leaves and sprouts bulbous clusters of lilac or pink flowers. The wild leek looks more like the culinary herb chives than the cultivated green and white vegetable abundant in supermarkets and winter allotments. Leeks have been a popular arable crop for centuries (featuring in Ancient Egyptian wall paintings ), so it’s possible the soldiers were rampaging through a vegetable patch, but it seems more likely they would have come upon the wild flower, which would be easy to identify and tuck into armour.

In Cymraeg ‘wild leek’ is cennin wyllt; the English translation neatly matching the Welsh. Other plants named cennin include chives: cennin syfi, garlic: cennin ewinog, and wild hyacinth: cennin y brain. In the Middle Ages, chives were known in English as ‘rush-leeks’, which leads me to wonder if, at the time of naming, cennin described a group of wild, bulb-forming plants with slender leaves, including the wild daffodil. Over time, as our relationship to our environment changed and plant knowledge that was once widespread dwindled, the words used to describe plants also narrowed. For most people today, the word ‘leek’ refers to the common vegetable, whereas in Cadwalladwr’s time cennin would have evoked a different scene; fields of lilac flowers, the fragrance of garlic leaves crushed underfoot, the start of spring.

Some speculate that daffodil leaves were confused with those of edible leeks at some point, similar in shape and colour. Others suggest the daffodil was adopted as a more appealing and sweeter-smelling alternative to the leek, promoted by former Prime Minister David Lloyd George . Whether this was an active choice to replace the original botanical emblem, or whether it stemmed from confusion surrounding translations of ‘cennin’, I do not know. It appears no one really does; the decision to employ daffodils lost to the passage of time.

Pedr is even more elusive, immortalised in anonymity alongside his cennin. While there don’t seem to be any popular theories as to who the famed Peter is, I would speculate that a plausible contender is St Peter, one of Jesus’ disciples. In Western culture, plants are often named after saints or prominent Christian figures, such as St John’s Wort, St James’ herb (ragwort) and marigold (after the Virgin Mary). One of the many Welsh names for wild daffodils is Blodau Dewi (‘David’s flowers’, after the Saint). It’s possible Pedr was also a canonised man, reflecting the prominence of Christian symbolism bestowed on the plant.

Additional Welsh names include Lili Grawys (Lent Lily), Blodyn Mawrth (March flower), Croeso Gwanyn (Welcome-the-Spring), Gwayw’r Brenin (King’s Spear) and - my favourite - Clychau Babi (Baby Bells) .

Cultivated daffodils don’t offer much to passing pollinators but the wild species, Narcissus pseudonarcissus, is an important source of pollen for solitary bees early in the year when wildflowers are scarce .

Underworld

Then senescence sets in. The flowers and leaves brown, wither and die, falling limply to the earth. Over time the roots contract, pulling the bulb deeper underground to more desirable conditions; preserved in cold dark dormancy.

In Ancient Greece, Narcissi were associated with death. The genus name Narcissus descends from the Greek ναρκῶ narkō, meaning ‘to make numb’, referring to the apparent narcotic and sleep-inducing qualities of the plant.

Whether the flower or the vain youth from Greek mythology was named first is unclear, but the the symbolism within each continue to influence the other. In Ovid’s version, Narcissus was a young hunter from Thespiae, considered beautiful by all who saw him. While pregnant, his mother Liriope had been warned he would have a happy life as long as he ‘did not discover himself’ .

Proud and arrogant, Narcissus rejects all advances from those around him. One spurned and bitter young man calls upon Nemesis, the god of revenge, condemning Narcissus to share his pain and fall in love with himself. Tiring from the heat of the day, Narcissus stops by a clear pool to quench his thirst. Seeing his reflection and not realising it’s his own face peering back at him, he becomes infatuated. Driven mad by this impossible unrequited love, his colour fades and body wastes away, leaving a single flower in his place, with ‘white petals surrounding a yellow heart ’. Though there are many flowers with white petals and a yellow centre, daffodils are associated with this myth due to the way many species thrive near water and the shape of their drooping heads, as though peering down at their own reflection.

Inspired by the fate of Narcissus, daffodils are associated with vanity. However, in Islamic tradition (featuring in the Qur’an), daffodils signify inner beauty, acting as metaphorical mirrors for self-reflection and the cultivation of virtues and spiritual growth .

The sixth century Persian ruler Khosrow I refused to be in sight of a daffodil flower during feasts, unsettled by what he perceived to be their ever watchful ‘eyes’. This resemblance is reflected in the Persian phrase narges-e šahlâ, the literal translation being ‘a reddish-blue narcissus’ ; a metonymy used by classical poets of the time to mean ‘the eye of a mistress’.

A second Greek myth featuring Narcissi as portends of death is that of Hades and Persephone. Persephone, the young daughter of the goddess Demeter, is picking flowers in a meadow when she sees a single golden daffodil. Enchanted by its beauty, she reaches for it, but Hades, lord of the dead, is waiting below. The ground opens up and he leaps from his golden chariot, grabbing Persephone and pulling her down into the depths of the underworld, where pale daffodils line the banks of the river Styx. The flower had been a trick, crafted to entice the innocent goddess in order to abduct her.

Grieving the loss of her daughter, and angered to learn that Zeus had previously promised Persephone to Hades, Demeter roams the earth in a black robe, causing all plants, flowers and crops to die, leading to famine. Panicked by this, Zeus negotiates with Hades for Persephone’s release. Hades agrees but tricks Persephone again, releasing her but ensuring her repeated return by feeding her pomegranate seeds; for if you eat in the underworld, you’re bound to return.

Seeing her daughter again, Demeter rejoices and the earth blossoms. But each time Persephone is required to descend to the underworld and be apart from her mother, life becomes cold and barren again, and the fruits of summer fade into the emptiness of winter, awaiting Persephone’s return and with it the start of spring.

The fate of Persephone by Walter Crane - Bridgeman Art Library: Object 349296. Image source: Wikimedia commons.

Returning

Dormant in the warmth, as the days cool the buried bulb starts to move. Invisible to all above ground, a new stem and leaves are quietly forming inside, pushing out old layers which brown and dry, creating a papery skin or ‘tunic’. Some Narcissus bulbs have been found to have as many as sixty layers, meaning sixty life-cycles; like rings in the trunk of a tree.

As the days lengthen, the new shoots appear, and so we begin again. Seeds may have scattered and germinated nearby, but the most effective way to increase growth is splitting bulbs. The initial main bulb, the ‘mother’, will produce smaller bulbs, the ‘daughters.’ When cultivating daffodils, the bulbs can be dug up, separated and planted in other locations. Left to their own devices the daughters will cling to the mother, sprouting their own shoots and flowers but remaining together as one plant.

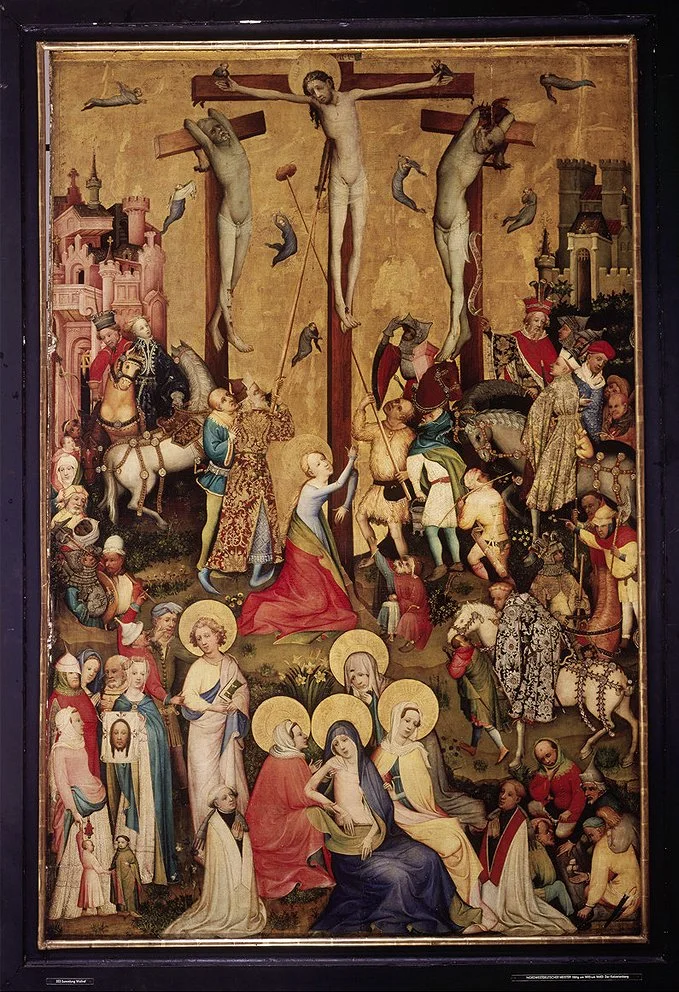

Representative of new life and renewal, in the late Middle Ages Narcissi began to be featured in Christian paintings, believed to be one of the plants that grew at the foot of the cross on which Jesus was crucified . According to some bible interpretations, it was St Peter who was first to see Jesus resurrected, possibly explaining the link between Pedr and daffodils, both synonymous with new life and hope.

Calvary scene c.1415, by the Westfälischer Meister in Köln (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne). Image source: Wikimedia commons.

Dewi Sant died on March the first in either 589 or 601 AD. Having spread the teachings of Christianity throughout Wales and beyond, his following continues to grow after his death. He was buried at his monastery where a shrine was erected, although this was destroyed in a fire in 645, and the resuscitations were repeatedly raided by vikings. The restored medieval shrine prevails however, at St David’s Cathedral, and has been a destination for thousands of pilgrims over the years; the journey considered akin to a pilgrimage to Rome, and three journeys equal to one to Jerusalem .

The daffodil’s relationship to Wales also continues to evolve. In the Black Mountains, one thousand feet above sea-level, the bio-research company Agroceutical Products grows and harvests thousands of Narcissi to extract Galantamine; an alkaloid naturally produced in the bulb that improves cognitive function in humans, used as a treatment to slow symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease .

Galantamine is also present in other wild plants such as snowdrops, but growing sites are limited, so cultivating daffodils offers an abundant source to make the much needed medication.

And so the seasons start anew.

With each golden bloom Persephone is once more returned to her mother on earth; the pilgrimage is complete. The daughter bulbs divide; the pollinators replete. Cennin Pedr continues to open its petals, to blow its trumpets, to ring its bells; if only for a short while.

In Welsh folklore, whomever is first to see a daffodil in bloom is considered lucky and will receive more gold than silver that year. But for some reason - whatever you do - don't point at it .

In the words of the holy man himself: ‘be joyful, keep the faith, do the little things you have seen me do.’ Dydd Dewi hapis.

Photos taken by Esther Williams in Hook, Pembrokeshire, and Coed y Bwl, Glamorgan.

References

Enwau Cymraeg Ar Blanhigion, by Dafydd Davies and Arthur Jones

Flowers and Fables by Jocelyn Lawton

New Persian English dictionary by Sulayman Hayyim, 1930

Vickery’s Folk Flora by Roy Vickery

https://www.stdavidscathedral.org.uk/discover/history/St-Non

https://lansugarden.org/things-to-do/events/lunar-new-year-crab-claw-narcissus-carving-workshop/

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/chinese-zodiac/rooster-chinese-zodiac-sign-symbolism.htm

https://www.welshwildlife.org/blog/welsh-wildlife-spot-february#:~:text=Both%20grow%20wild%20across%20many,of%20yellow%20in%20early%20Spring.

English broadsheet ballad circa 1630: https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/30222/xml

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/The-Leek-National-emblem-of-the-Welsh/

https://www.ancientartpodcast.org/blog/ancient-egyptian-cornucopia/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-12602857

https://www.worcswildlifetrust.co.uk/blog/seasonal-spot/dancing-daffodils

https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph3.htm#476975716

https://thursd.com/articles/flowers-in-the-quran#:~:text=The%20narcissus%2C%20also%20known%20as,and%20strive%20for%20spiritual%20growth.

https://archive.org/details/twocoloredbrocad00schi_0

https://academic.oup.com/jxb/article/60/2/353/634628?login=false

https://agroceutical.com/about/