October 31st, 2024

Nos Calan Gaeaf: Blood-wort, the Cailleach and Welsh Halloween

Welsh common names: Creulys Iago, Llysiau’r Gingroen, Llys Jacob

English common names: Ragwort, St James’s Herb

Scientific name: Senecio jacobaea

Tall and broom-shaped with a strong upright stem, the vivid yellow flowers of ragwort can still be seen flowering this time of year; blooming on plants that also bear wispy seed-heads that scatter in the wind. Common throughout the British Isles, ragwort is found in verges, meadows and roadsides, thriving in dry, rocky earth.

Common ragwort is a food plant of the striking red and black cinnabar moth, and the orange and black striped caterpillars can be found rampantly munching on the leaves in summer.

The English, Welsh and Latin plant names are all associated with St James; the English James derives from the Hebrew Jacob and the Latin Iacobus, which is similar to the Welsh Iago. The patron saint of Spain and fishermen, St James was one of Jesus’ disciples and it’s believed that ragwort bears his name as it's always in flower on his Feast Day, the 25th of July.

Blood-wort

Creulys, from the Welsh Creulys Iago, translates to ‘blood-wort’ or ‘blood-plant’, with Creu also meaning ‘to create, conceive or bring into being’, suggesting the blood that’s being referred to is specifically menstrual blood. This is consistent with the plant’s historic medicinal use as a treatment for amenorrhoea; a lack of menstruation or missed periods.

The 16th century herbalist John Gerard writes:

The Egyptians use the Sea Ragwort for many things (…) but principally thoseof the womb; as also the coldness, strangulation, barrenness, inflation thereof, and it also brings down the intercepted courses: wherefore women troubled with the mother are much eased by baths made of the leaves and flowers hereof.

‘Brings down the intercepted courses’ I believe means inducing periods, while ‘women troubled with the mother’ refers to those with uterine problems; mother being a common name for the womb in Gerard’s time.

Ragwort is not currently used to treat problems with menstruation, (unlike herbs yarrow and chamomile), and is in fact toxic to humans and poisonous to grazing animals, yet is an important plant for many insects and pollinators.

Additional Welsh names include llysiau’r ysgyfarnog, meaning ‘hare’s plant/vegetables’ (possibly suggesting ragwort was favoured by wild hares), and troed y frân, meaning ‘crow’s foot’, likely describing the angular shape of the stems or talon-like petals.

The Cailleach and Corn-Mare

In the Highlands of Scotland, at the end of summer when their harvest was complete, farmers were known to use ragwort, dock and corn to fashion an effigy in the form of a ‘hag’ and bestow it upon a neighbouring farmer who was still mid-harvest. The effigy represented a Cailleach; an invisible Celtic deity associated with creating landscapes, storms and harsh winter weather. Intended to drain the farmer’s stores, people feared being left holding the Cailleach; symbolically burdened with taking in the ‘old woman’ during the leaner months.

A similar harvest custom existed in Wales: a ‘harvest mare’ or caseg fedi was an ornament fashioned from the last tuft of corn standing that was ceremonially plaited and severed it from the ground by a flung sickle. Whoever managed to cut the sheaf would cry out:

Bore y codais hi,

Hwyr y dilynais hi,

Mi ces hi, mi ces hi!

Early in the morning I got her on track;

Late in the evening I followed her,

I have had her, I have had her!

This was then followed by the party asking: Beth gest ti? (What did you have?)

The answer: Gwrach, gwrach, gwrach! (A hag, a hag, a hag!)

Mare was a disrespectful term used for women and also a name for evil, preternatural beings. While there is what could be interpreted as a sinister sexual tone to the rhyme, given that harvest celebrations such as this were fun, family activities, it seems the verse is describing capturing a sinister ‘hag’ spirit, as with the Cailleach.

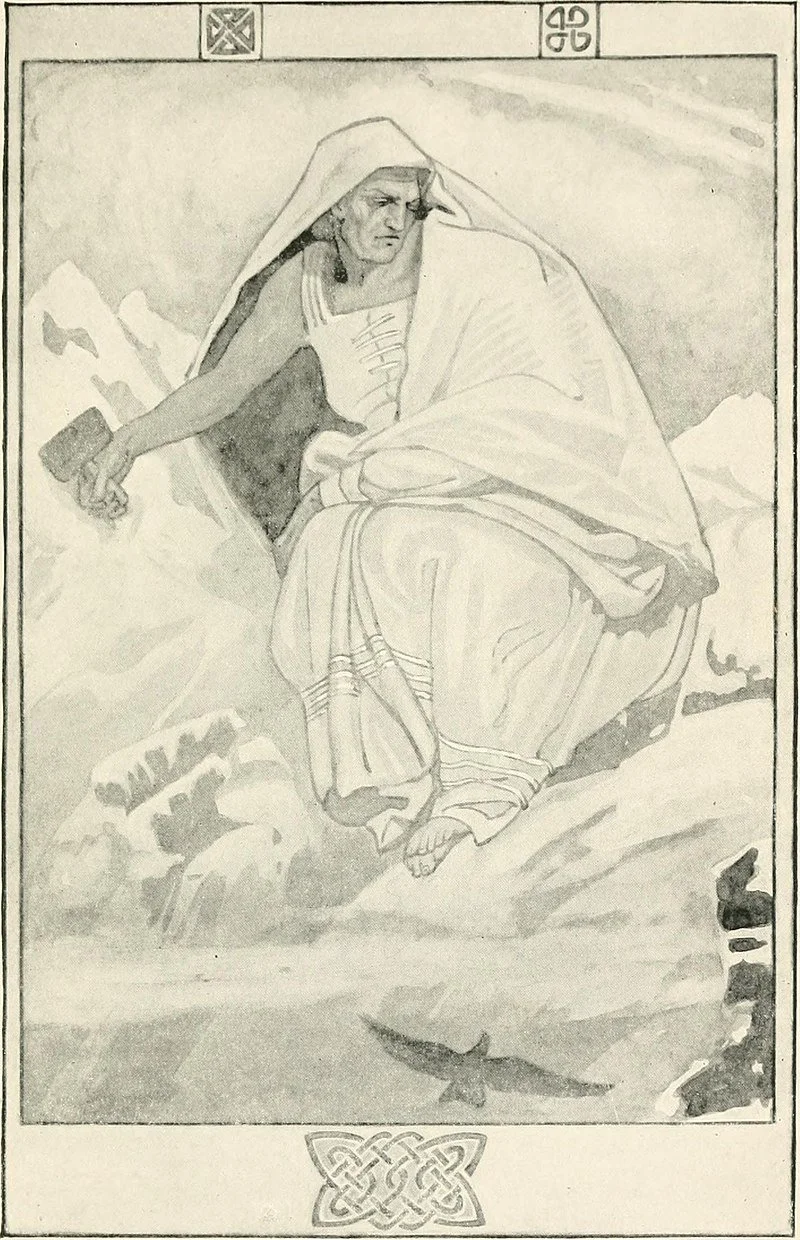

1917 illustration of the Cailleach by John Duncan in Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend. Image source: Wikimedia commons

The rigid broom-like silhouette of ragwort also gave rise to the belief that fairies and withes rode around on flying stalks, as featured in the 1785 Robert Burns poem, ‘Address to the Deil/Devil’:

Let Warlocks grim, an’ wither’d Hags,

Tell, how wi’ you, an ragweed nags,

They skim the muirs an’ dizzy crags,

Wi’ wicked speed;

And in kirk-yards renew their leagues,

Owre howcket dead.

Nos Calan Gaeaf - 31st of October

Nos clalan gaeaf, (or nos calangaua) is one of the three spirit nights in Welsh tradition, the tier nos yspridion - May Day, Halloween and New Year’s Eve - nights when the veil between this world and the spirit world is said to be at its thinnest, when spectral forms can be seen by those who dare to look. Translating to ‘Winter’s eve', the 31st of October was considered the beginning of winter and according to Welsh folklore, included many fireside games involving apple bobbing as well as love charms, divination, fancy dress and curious customs such as walking around the parish church three times at midnight before looking through the key hole to glimpse a ghost.

Witches in Wales

Welsh Halloween was traditionally more concerned with ghosts and the souls of the departed rather than witches; now a common feature in modern Halloween celebrations. While folklore does describe women practising witchcraft (such as Kate the Witch of Flanders, who could supposedly turn into a hare, and Dorothy Charles who caused a destructive thunderstorm the moment she died), belief in malevolent witches existed on a drastically smaller scale in Wales, compared to Scotland and England. During the witch hunts, almost 4,000 people - the vast majority being women - were executed in Scotland and 1,000 in England - yet in Wales it was just five individuals: Gwen ferch Ellis, siblings Lowri ferch Evan, Agnes ferch Evan and Rhydderch ap Evan, and Margaret ferch Richard.

This stark difference is bewildering. Academic Richard Suggett speculates that Wales’s Celtic influenced culture meant that beliefs in supernatural beings who interfered with daily life - such as fairies and pixies - was much more common, reducing the need to assign blame to a neighbour when someone became sick or animals died. Pembroke born author Phil Carradice suggests that the prevalence of the Welsh language at the time potentially safe-guarded women from accusations, as court trials were required to be in English, which many Welsh people didn’t speak. Carradice also surmises that rural communities in Wales were heavily reliant on wise older women and herbal healers who utilised medicinal plants, and were therefore less likely to ostracise them.

The relationship between women accused of witchcraft and their ability to harness the powerful wellbeing and healing properties of wild plants in their surroundings runs deep. The loss of common land following The Enclosure Acts initiated in the 1600’s, had a uniquely troublesome impact on single older women, significantly curtailing their ability to support themselves through foraging and grazing livestock, increasing their vulnerability and dependence on others, thus making them easy targets for persecution.

The links between the witch trials, women’s use of land, plants, and their role as healers and midwives is explored in Mona Chollet’s revelatory book Witches; Why Women Are Still on Trial, which I highly recommend. I came across Chollet’s writing in the BBC Radio 4 series Witch, by India Rakusen, which is a brilliantly produced fascinating listen, especially this time of year.

BBC Witch series by India Rakusen: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001mc4p

Nos Galan Gaeaf Hapus!

Photos by Esther Williams, taken in Hook, Pembrokeshire.

Disclaimer: don’t consume or use wild plants for health purposes without speaking to a medical professional first. Be cautious if foraging and only gather plants that you are certain of. These essays are intended to pique interest rather than act as a robust edible or medicinal guide.

References:

Flowers and Fables: A Welsh Herbal by Jocelyn Lawton

Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character by Marie Trvelyan

Vickery’s Folk Flora by Roy Vickery

Welsh Folk Customs by Trevor M. Owen

Welsh Names of Plants by Dafydd Davies and Arthur Jones

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-68413510

https://witches.hca.ed.ac.uk/

https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/address-deil/

https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=59

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/jacobean

https://geiriadur.ac.uk/gpc/gpc.html

https://www.exclassics.com/herbal/herbalv20029.htm

https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780708315507/page/100/mode/2up?view=theater